While you sleep I will take one.

Did she hear those words, or did she think them? Olivia wasn’t sure. Most people have voices in their heads, declarations of conscience, embedded beliefs, remembered conversations with parents and siblings both good and bad (although, perversely, it is the worst you recall the most). Her own inner voices tended to enumerate her flaws or promise some future doom.

I will take one. This voice sounded particularly murderous.

Her plan for this pregnancy was to find a bucolic mountain setting where she could read and passively enjoy the gorgeous views. She thought she’d found such a place in The Aspens, a sprawling silent retreat in the Colorado Rockies run by an order of nuns. She booked for late September when the aspen trees, cued by the shorter days, were at their loveliest, and her pregnancy would still be at a comfortable stage. When it was closer to her time, she would leave the retreat and return to Denver where she would give birth. Time away from the city would be calming and nourishing for her and the baby. Most importantly, Olivia wanted to avoid stress. Stress was in part what ended the other two pregnancies, or so she had been told. It wasn’t because she would have been a bad mother. It wasn’t because she did not deserve a child.

She hadn’t expected The Aspens to be so large. As her shuttle bus neared the end of the long driveway, the complex appeared to cover the hillside. They’d taken three neighboring Victorian houses and connected them. The driveway ended in a large parking lot full of cars around the back of the buildings. Who knew so many would be interested in a few weeks of silent meditation? But she was disappointed by the shabbiness: roof shingles missing, brickwork in need of repointing, warped boards. Should she make allowances because it was run by nuns? She supposed maintenance couldn’t be easy here in the mountains.

An elderly nun staffed the front desk. Olivia was surprised to see her in the traditional floor-length habit, starched white wimple, and black veil. Olivia didn’t know nuns wore those anymore. The sister’s tunic was rusty brown. She ran Olivia’s credit card and signed her in. “I’m Sister Agatha. I’m so pleased you will be joining us. Is your husband your emergency contact?”

“My brother is my emergency contact. I’m not married or attached. I have no one else.” She watched the sister’s face for judgement.

The nun looked up, smiled, and put both hands over Olivia’s. “Bless you. This will be a lovely respite for you and the baby.” Of course, Olivia was showing, but this was the first time a stranger called it out. She supposed it was good someone knew in case of an emergency. This was a silent retreat, so this should be their final spoken exchange until Olivia checked out.

The nun assigned Olivia a sunny room on the ground floor. She’d meant to ask for a first-floor room anyway to avoid the stairs. She was relieved. She didn’t want to take any chances.

Her window provided an uninspiring view of one corner of the parking lot, but, to her delight, if she looked a bit to the left three aspen trees displayed their charms, their flat yellow leaves making a gentle quaking sound as a breeze drifted through them. Farther up the mountain slope was a rare grove of red aspens, like arterial blood splashed across the hillside.

Olivia wanted to take a nap before the evening meal but felt a thrill of panic when she closed her eyes. While you sleep. She needed to get over this anxiety.

Dinner was served at six o’clock, signaled by three soft bells. The guests entered the dingy gray dining hall silently and sat at the places indicated by their name cards. She shared her table with five other people. She nodded and smiled, and they smiled back. No one spoke to her, but they weren’t supposed to.

She was surprised by the large number of guests—forty or fifty and a dozen or so nuns who sat together at a separate table with their heads bowed. These brides of Christ were in their seventies or eighties at least.

Two sisters served a thick vegetable soup with hard bread, washed down with goblets of water. Everyone was well-behaved except for two younger women—mid-twenties or so—who whispered back and forth, clearly unhappy with the food. Perhaps she was overreacting, but Olivia found it hard to eat listening to them. Between stomach pangs, she delivered pointed looks to no avail. The fact the nuns did nothing to correct them annoyed her.

After dinner, the guests were free to wander around the building and grounds. Olivia was tired but ventured out onto the large wraparound porch. She saw Sister Agatha give the two young women who’d whispered at dinner a note. They looked unhappy. Good.

High overhead drifts of smoky cloud floated leisurely through ribbons of orange and red. The sky was breathtaking, as their website promised. Olivia studied The Aspens website before coming here; she had seen the photos and videos, read the testimonials. She thought they promised too much. Of course, it was a beautiful spot, but there was nothing either vacation-y or even spiritual about it. An old house–or houses–in the mountains, and not in wonderful repair as far as she could tell, which offered only quiet. Built in the late 1800s, it had been variously a church, a school, and a boarding home. Maybe the nuns were so busy with their inner thoughts they hadn’t noticed the ongoing damage.

Back inside she took the long route to her room, along a gallery of open doors. The wallpaper in some rooms was torn and soiled, and she wondered again how the nuns allowed things to get this way without some attempt at repair. They could at least have kept the doors closed. Dust was thick and, in many cases, greasy looking.

She slipped out of her clothes and fell into bed. Sleep came as easily as the light going out. I will take one.

⁂

Olivia’s dreams were torturous, but the details forgotten upon waking. She had an upset stomach, but it was something she expected at this stage of her pregnancy. She looked forward to a silent day of contemplation, but then she heard the shouting outside her door.

“She wouldn’t have left without me! All her things are still in our room!”

Olivia slipped into her dressing gown and stepped out into the hall. The shouter was one of those young women from the night before, face to face with another elderly nun, who didn’t seem in the least perturbed.

“Perhaps she decided this experience wasn’t for her, dear. Not everyone appreciates these extended silences.”

“She wouldn’t have left without me! I can’t even reach her on her phone.”

“Cell reception here is spotty, I’m afraid. I’m sure she’s fine. I’ll take you to the Reverend Mother. I’m sure she can help.”

Olivia felt bad for the young woman, but not unhappy at least one of the pair was no longer staying here. Maybe that was cruel. She walked down to the small breakroom off the dining hall where she could get some tea and toast. She much admired all the Palladian and French door windows along this side of the house, prominent because of the bright, early morning sunlight. The panes created quadrilateral patches of brilliance which appeared in random locations on the wood-paneled walls and parquet floor, some following and some leading her along. She stopped, but the shiny patches did not. They gathered and flowed into the shadows at the end of the hall.

She distinctly heard crying. A tiny, upset baby. But children weren’t allowed here. Another rule breaker? In any group there always seemed to be at least one intent on ruining the experience for everyone else.

She returned to her room and read through lunch, forgetting to eat, and then had no memory of what she’d read. The idea of having to start over in the book where she’d left off yesterday disappointed her. She felt a mild cramping in her lower belly but didn’t feel hungry. She lay on her back and stared at the pinkish walls, which appeared to have breath, and sometimes perspiration. She fell asleep.

While you sleep I will take one.

Olivia woke up after dark. She glanced at her watch. Ten p.m.. She didn’t hear the bells and missed dinner. She’d be too awake and hungry to sleep. She’d brought her pills with her, but she wasn’t supposed to take them because of the baby. This annoyed her, but it was hardly the baby’s fault. There might be fruit in the breakroom.

When she got out of bed she felt a little woozy and had to grab the footboard. She heard that distant crying again. She knew some animals could sound like a baby crying, some birds, cats, porcupines. Doubtless there were all kinds of animals in the vicinity who might sound like a mewling infant.

She found a banana in the breakroom and sat on a bench eating it. Bananas contained potassium. Was that good for the baby? She had no idea. She refused to believe her earlier miscarriages had been her fault, although she was sure there were people who thought so: her mother and those two boyfriends, the fathers. But her mother miscarried once herself, as had her grandmother. Troubled pregnancies ran in her family. It was hardly Olivia’s fault.

Flashing red and blue lights bathed the dark hillside outside the windows. What now? She crept toward the front door, keeping herself hidden in the shadows. A group of nuns was standing in the entryway talking to two police officers. Olivia could barely hear them, but apparently the other bothersome young woman was missing as well. Perhaps she’d gone out searching for her roommate? The officers promised to patrol the area. Olivia returned to her room. She felt suddenly heavier and ill.

Of course, she couldn’t sleep, except for a few minutes here and there, interrupted, repeatedly. So multiple sleeps. She had no idea how many. I will take one. I will take one. She was thinking of her other babies, the ones she’d lost. They would have been toddlers now. Did she know how to parent a toddler? She had no experience taking care of anyone, and she hadn’t done that great a job taking care of herself.

To her surprise, the dads had wanted those children. She was somewhat grateful—she hadn’t expected them to take responsibility—but couldn’t imagine herself in a stable relationship. They weren’t bad men—they tried to be helpful—but once they learned she was pregnant, they attempted to take control. She supposed that was the way they were taught. But it complicated things. Relationships always complicated things.

Her last doctor suggested she not try to get pregnant anymore. “Too much risk,” he’d said. She could tell he thought she was promiscuous. But she’d hardly slept with anyone. He was condescending the way he spoke to her, like he wanted to be her dad. She didn’t need a dad.

Olivia didn’t know Tom’s last name, the father of her child-to-be. It seemed better that way, less complicated. She got to make all the decisions about where to live, what to feed the baby, how to raise it. She didn’t have either his address or phone number.

Too long she’d felt she had no control over her life. But this time was going to be different. She would have someone who would love her. He or she couldn’t help themselves. And she would make the rules. While you sleep.

When sleep came, it came without preamble. She was staring at the ceiling, and then she felt hands on her shoulders, her breasts, her belly. As if she were in an emergency room, and they had to move quickly. She remembered how Tom had touched her, no fumbling, and always with deliberate intent. He knew exactly what he was doing. But there was no passion in his face, and in his eyes not even a hint of warmth. I will take one.

He told her he loved her long hair, and kept stroking it, running his fingers through it. The next day she cut most of it off.

⁂

At breakfast the next morning, the dining room was less than half full, a dozen or so guests and a mere handful of nuns. The nuns were praying—at least Olivia could see their lips moving. She was the only one sitting at her table. The other name cards were there, but her tablemates hadn’t shown up. Perhaps they were sleeping in, or like her the day before, engrossed in some book or other. She felt a coldness in the pit of her belly which the warmth of the eggs and sausage failed to break.

After breakfast she walked around the ground floor. In some areas there were nasty drips on the baseboards and along the edges of the old carpet. Some of the furniture appeared not to have been dusted in years. She wondered what these nuns did with their time, but maybe they’d grown too old for proper housecleaning. She encountered no one in the halls or common areas. Where was everyone hiding? Some of the doors to the assigned rooms were open, the beds unmade, clothes tossed around, lamps on, tea and coffee cups on the side tables.

Olivia was so anxious she could hardly stand it. So much for a restful retreat. This wasn’t good for the baby. This plan of hers had been a mistake. She returned to her room, took off her clothes, and lay down. While you. While you. The next morning, she would ask one of the nuns to call her a cab. While you sleep.

She opened her eyes. She rolled over and looked at the clock. Time for lunch. She didn’t remember sleeping, and that bothered her. At least she hadn’t missed another meal. She was ravenously hungry.

She dragged herself into the bathroom and tried to fix her hair in the mirror. Noises, voices came from inside the drain. She kept playing with the light switch, but the bathroom light wouldn’t come on. She went back into the bedroom and turned on the overhead light, then left the bathroom door open, thinking she could see herself sufficiently to brush her hair. As she went from light into shadow and turned toward the mirror, it looked like there was a man standing in the gloom behind her, and she was holding something against her chest. The thing turned its head, a baby’s head with a twisted face. Its mouth contorted into a wail. Then the bathroom light blinked on, and she was by herself, looking wild and disheveled, but with no baby in her arms.

She burst into tears and ran back into the bedroom, sat down on the edge of the bed, and leaned forward, holding her lower belly. Only then did she realize she was in pain. She looked down and saw the blood spotting her panties.

Panicked, Olivia lurched to the bedroom door and opened it. She was practically naked and struggled to hide herself behind the door frame.

One of the nuns was standing in the hall, her head back, staring at the ceiling, muttering. The old woman’s chin quivered, the wattles on her neck looking painfully stretched.

“Sister!” Olivia called, and when the nun didn’t respond, “Sister, please!” The nun dropped her chin and stared at Olivia. It was Sister Agatha. “Something’s wrong. I’m bleeding!”

⁂

She heard women weeping. They might have been the nuns. It was hard to say.

Olivia was back in bed. She couldn’t remember how. A nun sat in the chair beside her, stroking her hand. Sister Agatha came into the room and offered her some tea. Olivia shook her head. Her face felt swollen, her nose stuffy. She’d been crying. “Did I, did I?”

“We took your blood pressure. It’s high. The doctor is on his way. He’s very good. We’ve been using him for years.”

Less than an hour later an elderly doctor was in her room examining her, taking her history, asking questions. Yes, her mother had had pre-eclampsia with all three of her pregnancies, as had two of her aunts. Yes, of course she knew she was at higher risk. “I’m not crazy,” she said.

The doctor looked surprised she’d said that. Well, of course he did. Olivia had to be more careful. She didn’t mention the disappearing people, and certainly not that threatening voice. While you, while you. What could he do about it anyway? He could diagnose her as crazy, put her in a hospital under restraints, bring in social services who might take the baby once he or she was delivered.

Instead, he put her on bed rest, with a promise to check in on her from time to time. “But there are no guarantees, you understand, that bed rest will help.” Of course. There were never any guarantees of anything. But she was willing to try anything to bring this baby to term. Delivering her child in such a peaceful setting surrounded by kind, silent women wouldn’t be so terrible. Then she could leave here with a beautiful child and start their new life.

The next time Sister Agatha came in, Olivia accepted her offer of tea. The nun helped her sit up in bed, arranged additional pillows behind and beside her, held the saucer while Olivia warmed her hands on the sides of the cup. It all felt extremely sweet.

“I’m afraid my silent retreat hasn’t been so silent, has it? I apologize for the disruption I’ve caused.”

“No apologies necessary, dear. Up here we take things as they occur. We’ve had to end the retreat prematurely, in any case.”

“Why? What do you mean?”

“The snow is coming early this year I’m afraid. Most of our guests have already departed ahead of the storm.”

⁂

Olivia slept almost all the time. It was hard not to, lying in bed, bored. While you sleep. She thought she should feel guilty but did not. People left of their own accord because of the snow, and before that for reasons unknown. She had no certainty she, or that voice within, had any responsibility at all for their departures. I will take one. At least now, stuck in her room, she didn’t have to bear witness to their absence.

She didn’t know how strictly she could follow the doctor’s orders. She anticipated lying in bed twenty-four seven would drive her insane. But she made herself stay in bed those first few days, getting up occasionally to use the bathroom. The nuns provided her with a bedpan, but she refused to use it. She wasn’t supposed to lift anything heavier than one of her books, but she had lost interest in reading. Sister Agatha brought her a radio, but it only appeared to play static. Still, she found that more appealing than the silence.

The nuns brought her meals to her. The same two nuns each time, Sister Agatha and one much older. “Are the other nuns still here? Are you the only ones left? Is it just the three of us in this place?”

Sister Agatha patted her hand. “Please don’t worry yourself, dear. It’s not good for the baby. We are all with God up here.” Of course, that didn’t satisfy Olivia, but she couldn’t bring herself to ask again.

The meals were all much the same: stews and soups and sometimes hard bread or crackers. Perhaps they were running out of supplies. Olivia got to know the older nun a bit better, the one who often sat in the room with her even though Olivia never asked her to. The woman spoke little and only had a few teeth which she displayed with a nearly constant grin. Olivia thought she might have an intellectual disability, although perhaps that wasn’t fair. Every few days she sneaked Olivia a candy bar as if it were a major breach of contraband, for which Olivia felt overly grateful.

Sister Agatha encouraged her to take a shower every day, and to at least put on a pair of clean underwear. Since the nun took care of Olivia’s laundry she would know if her advice was followed. They provided her with a shower chair from the nuns’ quarters which was “unfortunately no longer needed.”

It snowed off and on for a week, maybe two. The blazing whiteness rose to her windowsill. If Olivia rolled onto her side and stretched she could see part of the outside. Her yellow aspens had lost most of their leaves, the few remaining looking artificial, as if wired to the branches. But further up the hill she could still see splashes of red aspen against the sparkling white, and shadow shapes moving among the trunks. She couldn’t see them well, but she couldn’t shake the idea that this was where the missing people had gone.

Olivia knew with bed rest there was a danger of blood clots, back aches, depression, or even hospital psychosis. While you. While you. She supposed evidence of those first few things would be obvious, but psychosis felt like an old friend at this point. How would she know when she crossed the line?

Sometimes she felt dizzy and faint. Sometimes she was short of breath. She grew restless and kept changing the placement of her support pillows. She lay on her side with her legs bent, a pillow between her knees. She tried rolling her ankles and wrists in circles. Sister Agatha brought her a small ball to squeeze.

She stopped dreaming, but the inner voice persisted. While you. While you. Sleep. Sleep.

Sometimes lying in bed, she believed she was somewhere outside the house, hiding among the aspens, unable to get back in. She grew so cold she couldn’t move her limbs.

At least the building was well-heated, too much so. The furnace was loud, the pipes banging and echoing throughout the structure. Sometimes the nun sitting beside her made a pained face and clamped her hands over her ears.

While you sleep I will take one.

Olivia believed she was out in the snow again, the drifts creeping over her. She opened her eyes. She’d rolled over to the edge of the bed, almost fallen onto the floor. Her blankets had come off and covered the empty nun’s chair like a shroud. She listened for the furnace but couldn’t hear anything. She sat up and glanced around the room. Her finished dinner tray was on the table. The nun didn’t take it away last night. The door to the hallway was open. The light through the window was so improbably bright she wondered if it touched her if she would burn.

“Sister! Sister!” She heard no response, no sounds of movement, nothing. This made her lower belly hurt, but maybe the pain was from something else. She didn’t dare shout any louder. She might tear something open.

She moved her legs to the edge of the bed by the window and swung them out and down. She tested the strength of her feet. She didn’t feel strong, but she believed she could stand.

For a moment she stood in the heat of the window, waiting until her eyes adjusted to the glare. She crept closer to the glass, rested her forehead against the pane. She twisted her head one way, saw that the yellow aspen branches had fallen, the limbs broken by the weight of the snow. She twisted her head the other way until she could see the parking lot, and all those cars, now covered with mounds of snow. As many cars as there had been the first day Olivia arrived. Sister Agatha lied to her. No one had driven away. No one had escaped the storm.

Olivia made her way to the door. She felt so heavy. She was waddling. Had the baby dropped? She felt she might deliver at any moment.

“Where is everybody?” she shouted once she’d cleared the door. She saw no signs of people, but there were shadows galore. All the doors were closed.

At the end of the hall one of the nuns stood with her legs spread, fists clenched, head tilted toward the ceiling, muttering some sort of prayer. “Sister!” Olivia didn’t know which one. “Sister, please, what’s happened?”

The nun didn’t answer, so Olivia struggled to go to her, legs spread, one hand pressed against her back, the other waving around as if seeking a point of balance. As she walked she imagined she was rocking her baby inside, giving the child reassurance, even though Olivia didn’t feel it herself.

As she came closer she saw the nun’s rapid mouth, pale tongue darting up and down as if seeking water or air, and heard the words, clearer now. “While you slept he has taken them. He has taken them while you slept.”

Olivia grabbed one of the nun’s rigid arms and pulled it toward her. “Sister, please.” The nun dropped her head and stared at her, grinning. It was the older one, showing her broken and missing teeth. “Where’s Sister Agatha?” But the nun continued to grin, her eyes fixed and glassy. “This place, The Aspens, it’s disturbed, isn’t it? Has it always been like this? Did you know? If I’d known I never would have come here.”

The nun stopped grinning. “Oh, my poor fawn. Houses aren’t haunted. People are.”

Enjoy this story? Consider supporting our magazine with a small donation.

All donations will go towards paying authors for new stories, or website upkeep to ensure our stories remain free to read.

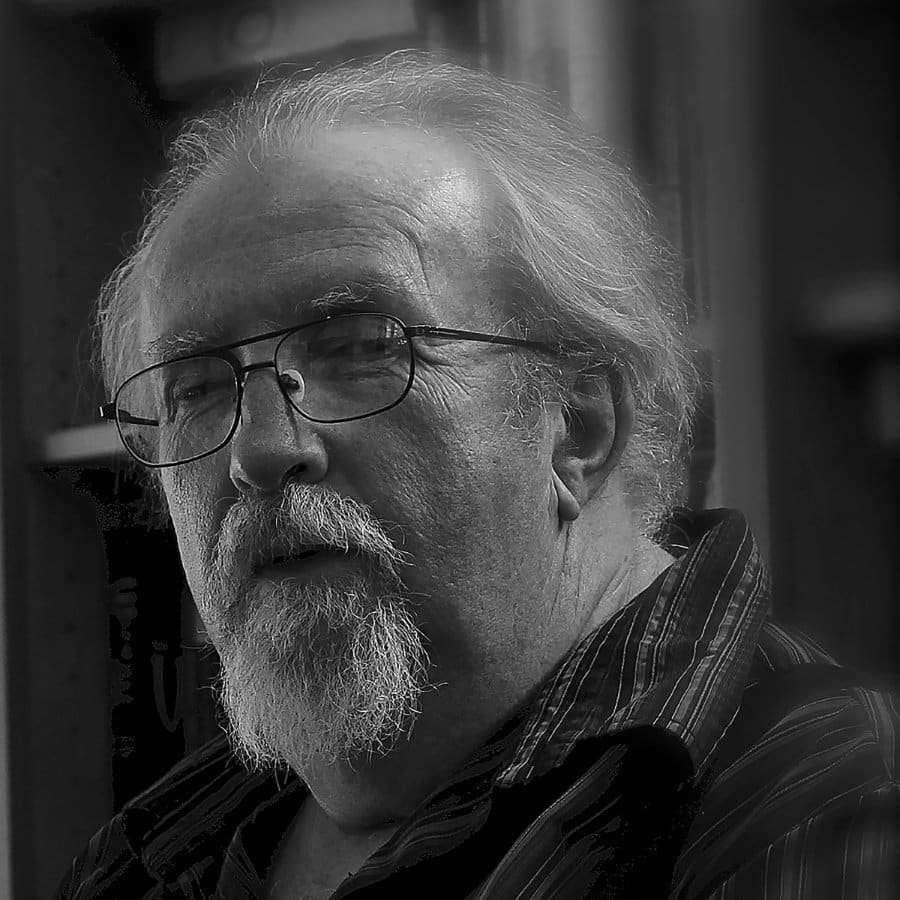

Steve Rasnic Tem has published over 450 short stories over the course of his 40 year writing career. Additionally, he has published poetry, plays, and novels in the genres of fantasy, science fiction, horror, and crime. His collaborative novella with his late wife Melanie Tem, The Man On The Ceiling, won the World Fantasy, Bram Stoker, and International Horror Guild awards in 2001. He has also won the Bram Stoker, International Horror Guild, and British Fantasy Awards for his solo work.

A transplanted Southerner from Lee County Virginia, Steve is a long-time resident of Colorado. He has a BA in English Education from VPI and a MA in Creative Writing from Colorado State, where he studied fiction under Warren Fine and poetry under Bill Tremblay.

Copyright ©2024 by Steve Rasnic Tem.

Published by Shortwave Magazine. First print rights reserved.

We believe in paying writers professional rates. We also believe in not hiding stories behind paywalls. These two beliefs are, unfortunately, at odds with each other. However, your support today could help us continue our mission.

We respect your privacy. We will never sell your information. You can unsubscribe at any time.